It’s time for more investment into health integration in schools

By Tami Alade, Health Associate at The Primary School

Isabella is a Latinx, full-time working mother of three young and vibrant school-age children. As a parent, Isabella was acutely aware of how much her children needed to be in school to support their academic and social development, but she also relied on school as a means to go to work every day. During the pandemic, all of the schools in her community shifted to remote learning, and most schools never reopened.

As a healthcare worker who was needed in-person everyday, Isabella relied on extended family to take care of her kids in the short term when remote learning was her only option, but it was a temporary fix that she couldn’t sustain forever. At work, she experienced the real and visceral impacts of COVID-19, and she saw firsthand that patients who were dying and being severely impacted by the virus were more likely to look like her and her children.

This was a common story that parents at our school in East Palo Alto, California, faced in the early months of the pandemic. And this was a common story nationally. We now have undeniable evidence that the virus disproportionately affected Black, Latinx, and Indigenous Americans, who were at higher risk of infection and death from the virus. As a result of higher COVID-19 case rates, students of color living in low-income communities were more likely to attend a school that never fully reopened, meaning that they spent a longer period of time not accessing the proven social-emotional, mental, physical, and nutritional health benefits of in-person learning. Schools that did reopen were more likely to be in high socio-economic, non-Hispanic white communities.

COVID-19 has forced us to reckon with the vast inequities that have long pervaded our healthcare and education systems. More than that, it has forced us to see that healthcare and education cannot be dealt with separately; they are inextricably linked.

inequities in reopening schools nationwide

In February, nearing the peak of the pandemic crisis, nearly 90% of Black students, 85% of Latinx students, and 81% of Asian students attended districts in California that were still primarily in distance learning mode, compared with 64% of white students. An abundance of evidence now confirms that schools can re-open safely with proper safeguards in place including universal mask wearing, social distancing, frequent hand-washing and ventilation. But early on in the pandemic, when crucial and timely decisions needed to be made, resources needed to create safe learning environments were not adequately deployed to schools, and the doors for Black and brown students remained closed.

As the Health Associate at The Primary School, I saw this situation play out firsthand. Last year, East Palo Alto, a community that is majority Latinx and Black, saw significantly higher COVID-19 case rates than neighboring high-income, majority white communities. The result was that we, along with all of the other schools in the community, had to make the tough decision to close our doors at the beginning of the pandemic and then, several months later, figure out how (and if) we could reopen safely. Fortunately, we were able to lean on a pre-COVID investment in health integration work, which included financial resources, relationships with families, and access to health care partners.

As we weighed the risks and benefits of reopening, we started by listening to the needs and desires of our families. Like Isabella, many of our families were grappling with impossible decisions: Do I forgo work opportunities to keep my child at home or do I send them to school understanding the heightened risk in our community? Do I protect those at higher risk living in my multigenerational home or do I allow my child to get the much needed benefits from in-person learning?

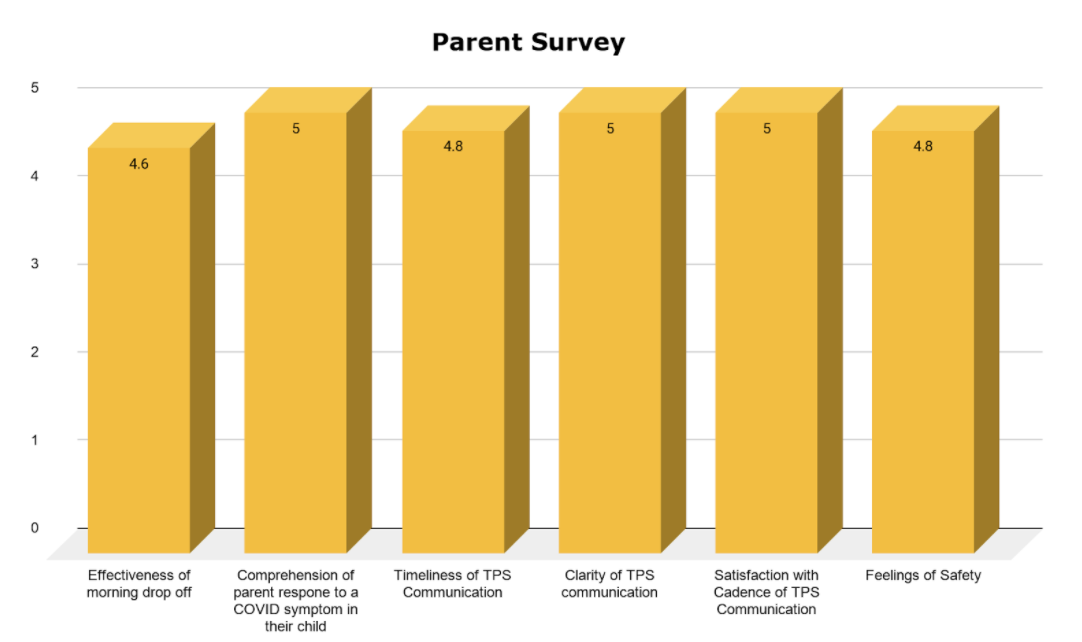

Yet, despite these many tensions, when surveyed in June 2020, over 75% of our families indicated a desire to come back and again in November when surveyed, over 80% indicated a desire to come to school. Comparatively, in a national survey conducted by researchers at USC, only about half of Black, Latinx, and Asian parents favored remote learning.

Building Off a strong foundation of health integration

So what about our approach gave families an increased sense of security and safety about returning in-person, despite the very real concerns surrounding the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 in their community?

For one, families already knew about our commitment to health. For example, before the pandemic, we were already teaching students as young as three years old about health practices like frequent and thorough hand washing. Furthermore, every year, we conduct hand washing observations and workshops with our students to promote quality hand washing in the classroom as a preventative measure to sickness.

Before the pandemic, students as young as three years old were practicing good hand washing habits in the classroom. When we shifted to remote learning, we continued to reinforce those habits through at-home activities.

In a similar vein, as part of our program, we use a parent-teacher space to help families set health-based goals (ex. “My child will stick to a consistent bedtime routine every night” or “My child will incorporate fruits/veggies into their meal _times/week”). We then partner with families to understand the why and how needed to implement these practices in their day-to-day lives.

The foundations of these practices made emphasizing health behaviors during the pandemic almost second nature, and while skills such as mask wearing and maintaining six feet of distance were new for everyone, holding conversations around the importance of these health practices was not.

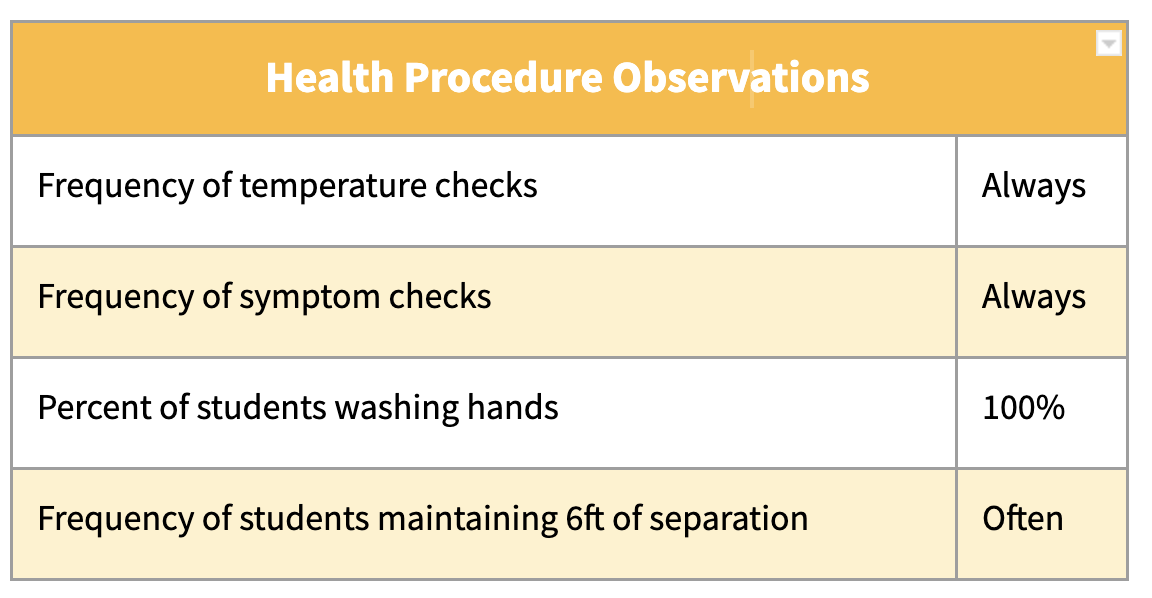

When we fully re-opened this past April, we kept building on these customs and made sure that our teachers understood and felt supported with continuing in-classroom practices that we already had in place, and implementing new ones (like checking temperatures and maintaining six feet of separation between students). Protocol fidelity observation checks were held to provide feedback to teachers around areas of strength and opportunity and a space was offered to strategize improvement processes.

In addition to this, we leveraged our partnerships with local community clinics to help families get access to earlier and easier testing, resources to understand the virus, and opportunities to connect with medical professionals about their top of mind questions.

While the pandemic was devastating in many ways, and required everyone to make significant adjustments in their lives, we were fortunate to have been able to build on this strong foundation of in-classroom practices and community partnerships as well as financial investment already in place.

What if more schools had been able to rely on a similar foundation going into the pandemic? Perhaps we would have been able to avoid such a prolonged period of remote learning in communities of color, and we wouldn’t be ending a difficult school year with even more challenges ahead — namely, addressing the widening achievement gap.

A Call to Action

This pandemic has been an inflection point forcing policy makers at the state and federal level to re-evaluate the ways in which we currently invest in our education systems. COVID-19 highlighted the essential role that schools not only play in educating children, but also in reducing food insecurity, promoting mental and physical well-being, and supporting the economy and workforce.

Federal and state investments have begun to hit the public education sector in ways unseen previously. California’s K-12 schools are slated to receive $28.6 billion in federal funds, and $129 billion in funding is reserved for national efforts. This funding could be used to double down on the intersections that tie education and health so closely together. More specifically, this funding could be invested in supports such as consistent social and emotional health and wellness supports for students, families and staff, health promotion programs for the entire school community that support key areas such as nutrition, physical activity and mental health promotion, as well as concrete supports that would allow ongoing health initiatives to take place (like on-site gardens, well-established gymnasiums and outdoor play areas, etc.).

Health and education are undeniably linked, and our continuous investment in a good-quality education is an investment for long-term, high quality health.

This crisis, in its own unique way, has given us — educators, health practitioners, and policymakers — an opportunity: we have the chance to come together and finally build a better and equitable system of care, one that our families and students deserve.